After analyzing 100 homilies, 10 lay talks, and 6 homilies by Fr. Barron, I want to present another aspect of worship and preaching that is little known to Catholics, namely that of an evanfelical megachurch. Everybody in Guatemala City knows la Fraternidad Christiana, commonly called "la Fráter," because it is the biggest evangelical church in town: it seats 12,200 people. Its construction was a national event: it was the biggest building project in recent times; the Catholic cathedral may seat 1,000, hence the evangelical temple is more than ten times bigger.

What account for the succes of this megachurch? It has none of the stereotpical traits often associated with megachurches: the pastor is not a charismatic superstar, his preaching is not flashy, and the worship is not bathed in emotionalism. Henceit is time now to turn to the socio-cultural dimension of homilies. Religion is an agency of cultural production contributing to the social identity and cohesion of individuals and nations. Homelists and preachers are cultural agents in their churches. Let us now compare the 100 Catholic homilies with a few Protestant ones.

La Fráter was started in 1978 by a 28 year old pastor, Jorge Lopez, with about twenty people. In 1985 he built his first sanctuary seating 750. In 1991 he opened an auditorium of 3,500 seats, but he needed more spece to grow. Construction for a 12,000 seat sanctuary began in 2001. The massive construction of nine buildings and a parking lot for 2,531 cars took several years. Now the church uses both, the auditorium of 3,500 and the megachurch of 12,200.

La Fráter was started in 1978 by a 28 year old pastor, Jorge Lopez, with about twenty people. In 1985 he built his first sanctuary seating 750. In 1991 he opened an auditorium of 3,500 seats, but he needed more spece to grow. Construction for a 12,000 seat sanctuary began in 2001. The massive construction of nine buildings and a parking lot for 2,531 cars took several years. Now the church uses both, the auditorium of 3,500 and the megachurch of 12,200.

The teachings of Pastor Lopez are best understood in relationship to his family background. He came from a very poor family that had no indoor plumbing and running water. His parents and grandparents were deeply religious, hence for Jorge religion appeared the normal way out of poverty, combining an evangelical spirit with hard work and savings. When he planted his own church in 1978, his goal was to create a new type of church, one in

which believers would reject the prevalent "Catholic" stereotype that "a Christian is poor, ignorant, and without social influence.

The teachings of Pastor Lopez are best understood in relationship to his family background. He came from a very poor family that had no indoor plumbing and running water. His parents and grandparents were deeply religious, hence for Jorge religion appeared the normal way out of poverty, combining an evangelical spirit with hard work and savings. When he planted his own church in 1978, his goal was to create a new type of church, one in

which believers would reject the prevalent "Catholic" stereotype that "a Christian is poor, ignorant, and without social influence.

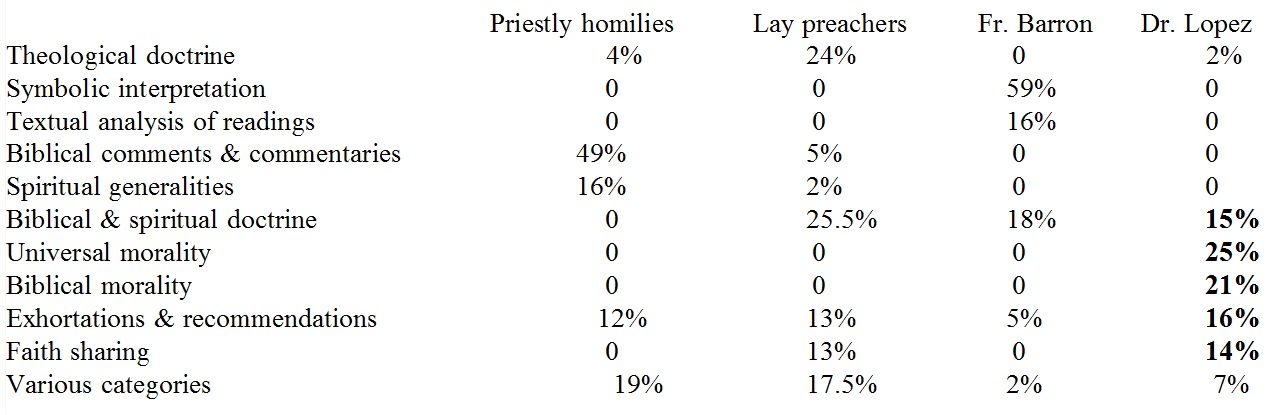

I have analyzed five sermons given on the Sunday before Easter of 2011, the same Sundays as Fr. Barron's homilies and those recorded in the Guatemalan parishes. The average length of these five sermons is 35 minutes, that of the US homilies in my sample is 10. Here are my quantitative findings:

By my definition, moral teaching deals with behaviors and rules of conduct, theological teaching with doctrine, and spirituality with attitudes and values. Morality may be further sub-divided into universal morality (e.g. the Decalogue in general, without any reference to the bible) and biblical morality (rules of conduct directly derived from scripture).

Marriage is a major emphasis in la Fráter which calls itself "a Christian church for the family." Dr. Lopez comes back to this topic again and again: his series of three sermons on "The Preventive Medicine for the Family" in July of 2011 was followed by a series of four sermons on "The Corrective Medicine for the Family." These were preceded in the spring by four sermons on "What a child needs," three of which were given before Easter, and to which I now turn.

The structure of these three sermons is simple: 35% of universal morality, 20% of biblical morality, 19% of personal stories, 18% of recommendations, and 8% of narratives. Rather than give examples from each category I will quote the pastor's personal testimonies which he uses to illustrate these moral principles.

The structure of these three sermons is simple: 35% of universal morality, 20% of biblical morality, 19% of personal stories, 18% of recommendations, and 8% of narratives. Rather than give examples from each category I will quote the pastor's personal testimonies which he uses to illustrate these moral principles.

The series on education is entitled "What a child needs;" these sermons emphasize that a child needs a model which usually is that of his parents. Numerous biblical references are given to bolster the argument, yet nothing is more convincing than the personal example of the Lopez family.

When Jorge celebrated his 59th birthday, his youngest son wrote him the following letter. "Dear papa. I give thanks to God for having given you one more year together with me; I love you, respect you, and admire you. Above all, I pray God to become like you one day, and be able to repeat the excellent and admirable model you have been for me... I thank you for your advice, words, and admonitions, because if you had not corrected me as a child I would not be the man I am today. Thanks for having been the best example in everything... I love you very much..." The same day the older son also sent him the following note. "Although I am 34, I continue admiring and respecting you. Or rather, only now can I really see the wisdom God has given you... and I continue learning from you ... I hope to be for my children exactly the way you were for me." Jorge was touched, and he keeps these letters in his bible.

Most important in Joge's upringing was his grandmother. "I had the good fortune to grow up with my grandmother, and each time I needed money I went to ask her and invariably she would say, of course, but first read to me Matthew 24, or read me the Psalm 91, and then she gave me money." The grandmother was illiterate. She knew the readings by heart, but she wanted both to hear them and to teach them. She was an outstanding example: for 30 years she took care of a grandson who was born paralyzed, deaf, mute, and epileptic. For 30 years "she had to give him a bath every day, feed him every day, take him outside every day, dress him and undress him every day." She gave her life for him. When he died, "I was very impressed to see my grandmother get on her knees and, with raised hands, give thanks to God for having taken him before her and for having allowed her to take care of him." Who would have taken care of him if she had died first? When the grandmother was about to die she called for Jorge. "In the early hours of the morning, she asked me to kneel at the side of her bed, put her hands on my head and said, ‘Lord God, make Jorge a servant of God, a preacher of the Gospel.' – Do you think that God does not listen to the prayer of a grandmother, mother or father? God listens, takes us, transforms us, and makes us good men and good women." Jorge's children fellow in his footsteps: they are all involved in church ministries. These stories illustrate the transmission of faith through the generations, yet story telling is only a small part of the pastor's sermons on child education.

The sermon of Easter day is totally different. There are no moral rules, no personal stories, only biblical doctrine (76%), theological doctrine (10%) and doctrinal descriptions (10%). This sermon endeavors to answer the question of "Why did Jesus rise again." The speech began with a vivid metaphor, that of the hamster endlessly running in the endlessly turning wheel. "So are we, running in a rat race, getting up at four in the morning, running, running, running, and the next day people continue running, running, running, for a day, a month, a year, ten years, a whole life." So why did Jesus rise again? - To give us hope. The rest of the sermon, or most of it, consists of New Testament quotations in reference to the resurrection. There are fifteen quotations or references, each one explained in a paragraph. In most of Dr. Lopez's sermons there are about as many quotations as there are paragraphs. This Easter sermon ends with, "For me Christ is life and to die is a gain," and how happy we are "to have a new life in Christ." This sermon is truly kerygmatic and mystagogical.

The sermon of Easter day is totally different. There are no moral rules, no personal stories, only biblical doctrine (76%), theological doctrine (10%) and doctrinal descriptions (10%). This sermon endeavors to answer the question of "Why did Jesus rise again." The speech began with a vivid metaphor, that of the hamster endlessly running in the endlessly turning wheel. "So are we, running in a rat race, getting up at four in the morning, running, running, running, and the next day people continue running, running, running, for a day, a month, a year, ten years, a whole life." So why did Jesus rise again? - To give us hope. The rest of the sermon, or most of it, consists of New Testament quotations in reference to the resurrection. There are fifteen quotations or references, each one explained in a paragraph. In most of Dr. Lopez's sermons there are about as many quotations as there are paragraphs. This Easter sermon ends with, "For me Christ is life and to die is a gain," and how happy we are "to have a new life in Christ." This sermon is truly kerygmatic and mystagogical.

Analysis and interpretation of the differences

There are six characteristics that make Dr. Lopez' sermons quite different from the priestly homilies: length, biblical teaching, universal and biblical morality, recommendations, and faith sharing. Pastor Lopez prepares his sermons in writing and memorizes them, occasionally adding a few comments to his text in the public delivery. His sermons are half hour well prepared speeches, not ten minute improvisations, hence his performances have a professional quality that is lacking in most homilies of my sample. He seldom repeats himself within or between sermons. His sermons are available at his church and on the internet; they are also for sale as CDs to respond to public demand and interest; the same cannot be said about priestly homilies.

His teachings are based on scripture in ways that are different from Catholic homilies, and reflect differences in training. Catholic seminaries emphasize philosophy and theology, that is, abstract thinking, while evangelical formation (if any, as some preachers are self-taught) emphasize biblical knowledge. For evangelicals like Dr. Lopez, the bible and Jesus Christ are the alpha and the omega; in the priestly homilies, it is church doctrine about the bible and Jesus Christ that form the basis of Sunday teaching and seminary training. Usually homilists only quote the assigned readings of the day and seem oblivious of the rest of the bible. Evangelicals (and Dr. Lopez) tend to interpret the bible literally while the homilists in my sample seem to follow no particular exegesis, and at times misinterpret the literal meaning of the text.

The absence of moral teaching in the 100 homilies of my sample was unexpected, as they contain no references to church rules (besides the mandatory Sunday Mass attendance), universal morality, or biblical moral norms. What we have, instead, are general exhortations (12%). In my analysis I collapsed exhortations and recommendations, yet a secondary analysis makes it clear that priests give general exhortations, while Dr. Lopez makes concrete recommendations. For instance, "Kiss your children, embrace them. The legacy we leave them is not a bank account but an emotional account." Recommendations like this one are intertwined with personal childhood memories and the examples of the Lopez family. Most of Dr. Lopez' moral teachings are about universal morality (25%), that is, rules of conduct known to the audience but in need of reinforcement. Although all priests are familiar with basic morality, it is not the major emphasis of Catholic moral theology, which concentrates instead on specialized ethics, e.g. sexual morality and bioethics; hence it is not surprising that homilies mention abortion but not the Ten Commandments.

Faith sharing – a major staple of the evangelical died – is absent in the homilies but common in the lay talks (13%) and Dr. Lopez (14%). Biblical and spiritual doctrines, absent in homilies, are central in lay preaching (25.5%), Fr. Barron's Sunday commentaries (18%), and Dr. Lopez' sermons (15%). Instead of biblical doctrine, priests offer general comments vaguely related to the readings of the day (49%) and spiritual generalities (16%), which are absent in lay talks and the Fráter sermons. These data suggest that lay homilies and evangelical sermons, as well as Fr. Barron's commentaries, are firmly anchored in the bible – for lay preachers, the Bible is the only training they have achieved through personal readings – while priests seem removed from biblical knowledge.

In sum, priests are not strong actors of cultural production, contributing to the moral, social, and doctrinal identity of their parishioners. Why is this so? I will offer two hypotheses, the weakening of the ethic of obedience, and the indirect effect of celibacy.

Obedience is a basic moral requirement of social life. The ethic of obedience is spelled out in St. Paul's letters: "Wives, submit yourselves to your husbands... The husband is the head of the wife... Children, obey your parents... Slaves, obey your earthly masters" (Ephesians 5:22 - 6:5). In non-differentiated societies where all social relations are based on inequality and subordination, this ethic covers nearly all aspects of life. The various moral obligations were further spelled out in the duties of one's state of life which made the ethic of obedience all encompassing.

People go through or belong to various stages of life (or life statuses), from being a child, an adolescent, a husband or wife, a student, a worker, an employer, a boss, a neighbor, a parishioner, a citizen, to finally becoming a grandparent. Thus before going to confession people in the past had to examine their conscience about the duties of their life statuses, e.g. for a child about having done the homework regularly, paid attention in class, collaborated with others in play, done the daily house chores, obeyed the parents promptly, etc. A list of the various duties of one's state of life took many pages in the missals of the past.

The notion of duties associated with one's state of life or life status seems to have disappeared; I have not heard it mentioned in the last thirty or forty years. Yet without it, the ethic of obedience is empty, for lack of specificity. The ethic of obedience is somewhat obsolete in differentiated societies which rely on participation and professionalism, yet even in technologically advanced societies, a student is expected to do homework, husbands and wives to perform the duties assigned to them by common agreement, and employees of all categories to perform according to the demands and wishes of their employers. In short, the homilists' failure to describe the various duties incumbent on everyone depending on their life status makes the ethic of obedience empty; hence, the Sunday homilies make little or no contribution to the social construction of morality due to the weakening of the ethic of obedience.

Celibacy is another factor of social disengagement. The priests' introduction into the clerical life style consists of spending six or seven years in comfortable seminary seclusion, without worries about food and lodging, and no student loans to be paid back over many years. After the seminary they become paid functionaries of the church – as "priests" rather than "prophets" or missionaries – always being assigned to money generating positions. As a consequence, celibate priests are as different from lay people as the upper class from the working class. Like millionaires, they will never have to worry about finding and keeping a job, having adequate health insurance, paying for a house mortgage and their children's education, and facing the unexpected expenses due family illness, addiction, lawlessness, or over-spending; better than millionaires, they are usually free from shopping addiction or an extravagant life-style. This removal from the wears and tears of secular life shows up in the homilies as they have nothing to say about it.

According to a 2011 study by a Central American agency, 80.8 percent of the Guatemalan population suffers from food insecurity, while at about that time in the U.S., 22.7 percent of home mortgages were "under water," that is, greater than the value of the house – 50 percent in Arizona, 46 percent in Florida, 36 percent in Michigan, etc. – but priests do not participate in the general insecurities of life in food and shelter, hence are unable to address these issues in their homilies.

Priests profess a spirituality of sacrifice and abnegation by following of Christ in his passion, at least symbolically through the sacraments and the sacrifice of the Mass. They believe to be "set apart" for this mission; as a consequence, their whole existence tends to be geared to the cultic performance of sacraments. Yet this spirituality and cultic conception of sacraments is increasingly questioned or even rejected by the upward mobile middle class of Lsatin America, zand even in the Western societies generally.

GO TO: PROSPERITY GOSPEL