Devotions declined precipitously over the last fifty years, but they were very popular in the pre-Vatican II days, as anybody old enough can remember.  Here are some data about high devotional achievements.

Here are some data about high devotional achievements.

Among the devotions of the pre-Vatican II church, none was more popular than the recitation of the family rosary. This devotion was brought to new heights in 1943 by the Rosary Crusade. "The crusade achieved an extraordinary success, with mass rallies across the United States and Canada," according to a newspaper report. Other Marian devotions were novenas, the use of medals and scapulars, and May Day celebrations.

Among the devotions of the pre-Vatican II church, none was more popular than the recitation of the family rosary. This devotion was brought to new heights in 1943 by the Rosary Crusade. "The crusade achieved an extraordinary success, with mass rallies across the United States and Canada," according to a newspaper report. Other Marian devotions were novenas, the use of medals and scapulars, and May Day celebrations.

Devotion of the Sacred Heart was also very popular. A picture of the Sacred Heart was to be "enthroned" by the parish priest in a prominent place in the homes in order to elicit "a permanent state of devotedness and love" of the Sacred Heart. Associated with this devotion were the communion and confession on the First Friday of the month, a holy hour on Thursday nights, and prayers of reparation and expiation. In the Archdiocese of Chicago, by 1946, "Almost 500,000 enthronements had taken place, with 13,465 registered night adorers, and about 40,000 youngsters pledged to spread the devotion in their homes," according to O'Toole (Habits of Devotion, p. 61).

A simple form of prayer was the daily "morning offering" of the Apostleship of Prayer, usually at the intention of Holy Father. The Eucharist has always been central to Catholics, with the paraliturgical devotions of the Forty Hours, nocturnal adoration, the benediction of the Blessed Sacrament, and Eucharistic congresses.

A simple form of prayer was the daily "morning offering" of the Apostleship of Prayer, usually at the intention of Holy Father. The Eucharist has always been central to Catholics, with the paraliturgical devotions of the Forty Hours, nocturnal adoration, the benediction of the Blessed Sacrament, and Eucharistic congresses.

Then came Vatican II and the spirituality of baptism, instead of the spirituality of frequent communion and confession. The Dogmatic Constitution on the Church mentions baptism twenty times, Holy Communion twice, but not confession and devotions. I will develop this point next month.

In a sociological perspective, a strong society is characterized by its strong subculture. The pre-Vatican II subculture was strong because of its vibrant devotions. Today the Catholic subculture is much weaker, and open to be invaded by secular influences.

THE RELIGIOUS IMAGINATION

All societies have collective memories. In pre-Vatican II Catholicism, it is devotions that mostly populated the collective memory. As devotions fade away, the collective memory becomes empty; then Catholics go through life without the map of memories and easily become secularized, as their memory is fuzzy with no clear sacred focus.

Collective memories always involve images. Between 1850 to about 1950, the mass production Catholic devotional art is known as "Sulpician art" (like the pictures above); it produced thousands of cheap plaster statues and pious images of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and Mary, of Therese of Lisieux, and Saint Anthony. This international Catholic art was totally divorced from secular art. To this day, the Catholic art of devotions is mainly divorced from secular art. Here are a few examples.

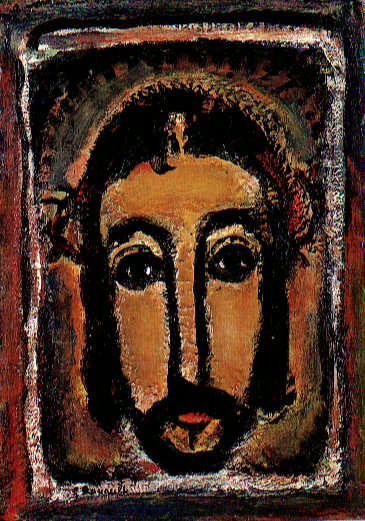

1. The Paris Sacré Coeur of 1875 and the London Westminster cathedral marked a turn to byzantine art. Today many

religious communities in Europe use Byzantine icons for worship (like the ones on the left), but as of 2013, I haven't seen any or many in the U. S.

religious communities in Europe use Byzantine icons for worship (like the ones on the left), but as of 2013, I haven't seen any or many in the U. S.2. Impressionism and Cubism were basically ignored in Catholic iconography. George Rouault produced deeply religious art in the 1920's; his work can be seen in museums but no similar work in churches.

3. The father of surrealism, Salvador Sali, produced "The Sacrament of the Last Supper" in 1955. It expresses a rich theology of the Eucharist. It is the most popular work of art of the National Galery of Art in Washington. It still has to make its way into the Catholic imagination.

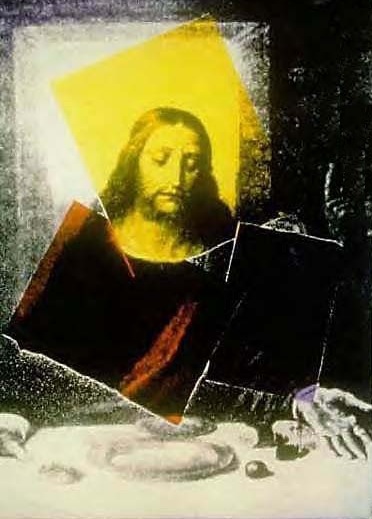

4. What about the few versions of the Last Supper by Andy Warhol (circa 1986)—see picture to the right— when will it make it into the Catholic consciousness?

(There are a few outstanding exceptions like the work of Matisse at the Vence chapel—I have incorporated a few of his pictures into the logo of the index file.)

(There are a few outstanding exceptions like the work of Matisse at the Vence chapel—I have incorporated a few of his pictures into the logo of the index file.)

In summary, the religious imagination provides a map of the spiritual world and a sense of how to navigate through it; witiout it, one is like a wanderer in a foreign land. Traditional devotions are/were associated with an imagery that today seems old fashioned and obsolete. Art is not a luxury. In the absence of artistic creations, there will mainly be kitch and no attractive spiritual map for the cultural elite.