Church doctrine ......... 24%..........4%.................0

Symbolic interpretation ........0.............. 0.................59%

Biblical & spiritual doctrine ......25.5%........0.................18%

Textual analysis of readings ........ 0.............. 0................ 16%

General comments & commentaries ....5%.......... 49%...............0

Spiritual generalities ......2%......... 16%.............. 0

Exhortations & recommendations ....13% .........12% ..............5

Faith sharing ... .. .13%......... 0....................0

Prayer .... 10.5%...... 0................... 0

Inaudible ...... 0.............. 8%................ 0

Dispensable ..... 0...............6%. ...............0

Various categories ... 7%........... 5%................. 2

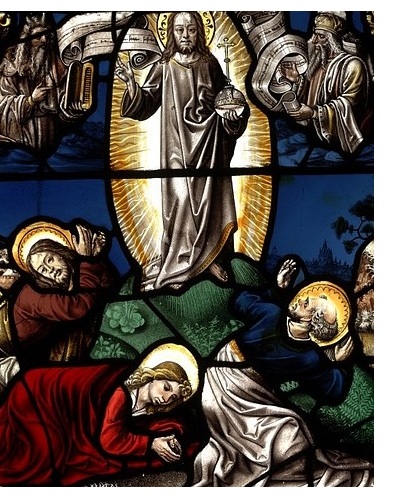

What is new here is the symbolic dimension which predominates all others (it counts for 70% of his five Lenten homilies), but more generally, what is new is the centrality of his focus. Let us review the five Barron Lenten homilies and their parish equivalents. The first begins with, “The story of the Transfiguration just haunts us,

because it speaks to the very heart of the Christian faith: the mystery of who Jesus is.” Eighty-four percent of this homily is the analysis of symbols. “Mountains in the Bible are meeting places of the divinity and the humanity.” This homily concentrates on mountain top or peak experiences. “On the mountain, Jesus was transfigured, in Greek metamorphein, to go beyond the form, a caterpillar becoming a butterfly, a seed becoming a flower; here the light of the transfiguration is a symbol of this metamorphosis. The form of Jesus is not left behind; it is transfigured, transformed into a higher register... Transfiguration and resurrection mean the same thing, meta-morphoses. The risen Jesus is not beyond the body, he is an embodied presence.”

because it speaks to the very heart of the Christian faith: the mystery of who Jesus is.” Eighty-four percent of this homily is the analysis of symbols. “Mountains in the Bible are meeting places of the divinity and the humanity.” This homily concentrates on mountain top or peak experiences. “On the mountain, Jesus was transfigured, in Greek metamorphein, to go beyond the form, a caterpillar becoming a butterfly, a seed becoming a flower; here the light of the transfiguration is a symbol of this metamorphosis. The form of Jesus is not left behind; it is transfigured, transformed into a higher register... Transfiguration and resurrection mean the same thing, meta-morphoses. The risen Jesus is not beyond the body, he is an embodied presence.”

In the parishes, one homilist spent seventy seconds repeating the story of the Transfiguration. Another mentioned it briefly: “Mount Tabor means mountain of light. We must also see the light of Christ... Let us pray to be able to discover the face of God as the three apostles did.” A third did not mention the Transfiguration at all, and a forth one was inaudible that day. Why is it that the Transfiguration does not haunt these homilists?

St. John’s chapter about the Samaritan women is presented as a symbolic story. “Wells are associated with marriage: Isaac and Rebecca, Jacob and Rachel, Moses and his wife... What is proposed here is a marriage between Jesus and the human race.” “St Augustine saw the well as a symbol of concupiscent desire, of addictive desire. We go back to the well of money, power, and pleasure, and we are thirsty again...” “My water is a well for eternal life, a well of grace. He who drinks this water will not thirst again.” The conclusion is a mystagogical invitation: “God has come into flesh; now is the time for marriage, now is the time for right worship, and then we will find water welling within. This story is about everyone.”

On this weekend of March 26-27, 2010, the first homilist did not mention the story of the Samaritan woman; the second re-told the story, adding, “Today like 2000 years ago, women are despised. Jesus touched her life.” The third recounted the story as an encounter with God, “Deep down we have a deep desire for God; it is fulfilled in baptism.” The last one explained that “The living water is faith. Some people have everything but are not happy because they have no faith; others are poor but have faith and are happy.” There is little here on the symbolic “marriage between Jesus and the human race” by drinking from the fountain of youth, the well of “water springing up to eternal life.” In contrast to these parish homilies, the lay talk “Woman, if you knew [the gift of God],” has a lot to offer.

The story of a man blind from birth is the “archetypal story of coming to spiritual vision. We were all born blind through original sin which obscures the mind.” “This is a story of re-creation, of making things new, starting at the beginning again, because Jesus is the creative word of God.” This homily is totally symbolic, in contrast to the homilies in the parishes on that same day.

One homily of eleven minutes had no main idea. A second one developed the theme that “Christ is the light of reason and the light of faith.... The blind man of the gospel said, ‘I believe;’ and faith changed his life.” The third one described three ways of being blind, one of them being the man blind from birth, but offered few comments.

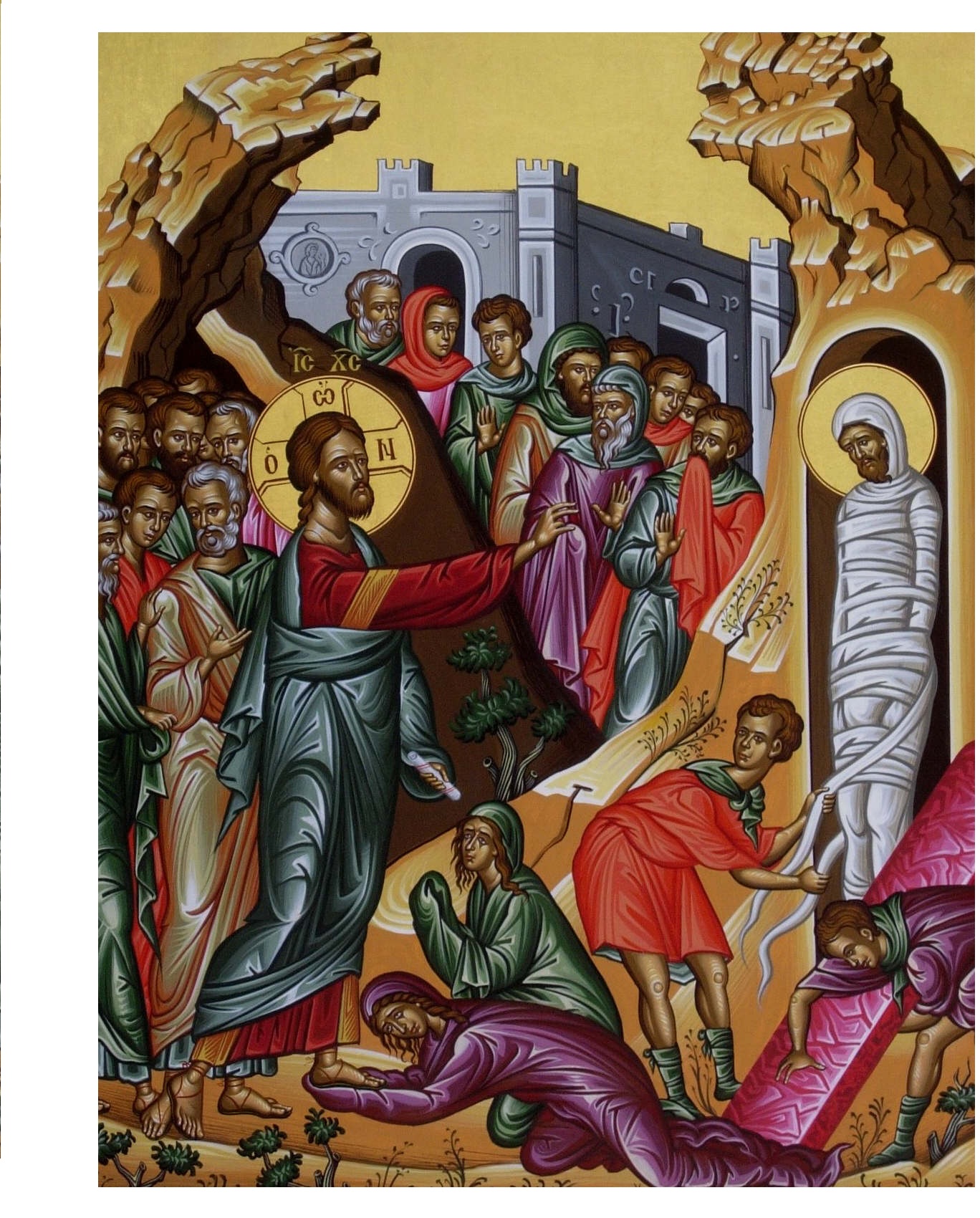

In contrast to Fr. Barron’s previous homilies, the one about the death of Lazarus is all

theological and spiritual doctrine; there is little symbol analysis here. “Throughout the Bible, God’s glory is manifested in his life giving, his creative work. God’s glory will come in creative manifestation... Death is not final, it is only a sleep, a transitional state for a richer mode of existence.” “I am the resurrection and life. Jesus is the life” (explained in reference to Exodus). Death is “the central tragedy of human life. There is a terrible sense of loss at the death of someone we love. Remember the days you were weeping. I remember the death of my father...” But death is not final. “God’s word in Jesus Christ is more powerful than death.”

theological and spiritual doctrine; there is little symbol analysis here. “Throughout the Bible, God’s glory is manifested in his life giving, his creative work. God’s glory will come in creative manifestation... Death is not final, it is only a sleep, a transitional state for a richer mode of existence.” “I am the resurrection and life. Jesus is the life” (explained in reference to Exodus). Death is “the central tragedy of human life. There is a terrible sense of loss at the death of someone we love. Remember the days you were weeping. I remember the death of my father...” But death is not final. “God’s word in Jesus Christ is more powerful than death.”

On April 10, 2011, one homily was inaudible while another developed the theme of “coming out the tomb of sin through confession;” the words confession and reconciliation were repeated endlessly. That same day a third priest gave an inspiring homily ending with “Levántete [stand up!] Sale de aquí! [come out of here!] Amen!” followed by long applause from the assembly. This was a remarkable mystagogical homily. The other two homilies of Fr Barron and their parish counterpart lead to similar conclusion.

Conclusion: cultic priesthood versus mystagogy

A high expectation of preachers would be to be heard by all, even in the back of the church, and to be listened to by the audience most of the time. To foster attention, the preacher must constantly “work the crowd” to keep its attention. A reference at the beginning of the homily to the news of the day – the royal wedding of Prince William and Kate or the end of the world to happen that very day – draws immediate attention; the challenge is to keep it. Homilies and funeral eulogies are the only forms of monologue that are still commonly respected and tolerated, but for how long?

To be empowering, a homilist must impart his wisdom to the audience. The dialogical homilies observed in Guatemala are a step in this direction (although explicitly forbidden by canon 767 of canon law). Fr. Barron’s homilies are recorded for television in his library-office, not a church; one feels that he is speaking directly and personally to the viewer as if he were only a few feet away. His language is colloquial, like a dialogue between you and me. His content is reflexive, like a meditation on the human condition. So are the lay talks presented above. Any homily with a mystagogical message is empowering when it empowers one to apply it.

The appropriation of biblical texts and symbols is achieved through daily Bible reading. In both 1990 and 2005 only 13% of recently ordained priests said they read the bible daily (Hoge, Experiences of Priests Ordained Five to Nine Years). I heard in both Catholic and Protestant circles that one should memorize a fwew biblical verses per week, but this advice was addressed to lay folks, not priests. In an interview of seminary faculty, one mused, “I am always amazed, and somewhat appalled, at the negligible interest seminarians show in using the Scripture as a place of encounter with God” (Schuth, Seminaries, Theologates, and the Future of Church Ministry). This would probably apply to many.

Emotionality is as basic in homiletics as persuasion in rhetoric. Emotionality provides a catharsis of negative emotions and elicits the pathos (passion) of positive ones. A good homily (like a good funeral eulogy) heals the wounds and gives faith, hope and love, the basic Christian e-motions. Mystagogy. Max Weber contrasted “priests” as cultic functionaries with “prophets” who operate outside the confines of the temple; I would rather oppose here “priests” and “mystagogues.”

Mystagogy is a pedagogy into the divine mysteries. If the scriptural text is the “sacrament” of Christ for the church, then Fr. Barron and the lay preachers are mystagogical because they centered on the biblical text. Priests cannot be mainly cultic performers; they must also be mystagogues. Homilies must be more than general comments about the readings. They are mystagogical when they express the spiritual experiences of the speaker rather than his opinions or church doctrines.

P.S. : Preaching models

1. The most common model in priestly homilies consists of making general comments about the readings; these comments are often only vaguely related to the text of the readings; they are only related to the themes of the readings.

2. Fr. Barron offers textual commentaries, that is, an analysis of a biblical text, as in published biblical commentaries. They are rare in priests’ homilies.

3. Homilies centered on church teaching rather than scripture; such teaching is occasionally found in priests’ homilies in the form of catechism.

4. Sermons based on biblical teachings, that is, a theology inspired directly from biblical texts, e.g. sin or salvation. This model is common in Protestant sermons.

5. Faith sharing. It is common among evangelicals and lay preachers; it is also a major trait of St. Paul’s letters.

6. Homily/sermon involving prayer. It is common among evangelicals and lay preachers. Pervasive in St. Paul’s letters.

7. Homilies on spiritual teaching, e.g. on trust in God. It is common among priests in the form of generalities.

8. Exhortations. They are often associated with spiritual teachings; they are common in priestly homilies.

9. Preaching leading to recommendations. It is rare in priests’ homilies, but common among evangelicals and lay preachers; it is also common in St. Paul’s letters.

10. Preaching centered on moral teaching It is not found in priests’ homilies but in Protestant sermons, often associated with practical recommendations. I will provide an example in my next post.

11. Homilies involving exegetical interpretations, either a literal/fundamentalist interpretation, based on the historical-critical method, or involving spiritual and symbolic interpretations. The historical-critical method and symbolic interpretations are not found in priests’ homilies.

The models most conducive to intellectual mystagogy are textual commentaries, theological and biblical doctrines, faith sharing, prayer, and spiritual teachings. The models most likely to lead to a mystagogy of deeds are faith sharing, spiritual teachings with recommendations, and moral teachings.

GO TO: FIVE EVANGELICAL SERMONS